![]()

Economy of Design

Year - 2023

Jephtha

Royal Opera House

Following a successful collaboration with the creative team behind The Royal Opera’s Rigoletto (2021) and many projects in between, set designer Simon Lima Holdsworth returns to Covent Garden for Jephtha. But how to approach a rarely-performed and even rarer-staged oratorio, whose biblical source material and Enlightenment-era spirit demand sharp juxtapositions: of light and darkness, of glory and despair and of certainty and doubt. As he looks back on the process of creating Jephtha’s design, and on his own process as a designer, Holdsworth explains what he wants – or doesn’t want – us to take away from the production.

Eloise Giegerich: How do you approach a new project and how did you approach Jephtha?

Simon Lima Holdsworth: I begin each new project from a clean slate. For Jephtha, I began with the piece itself; I only read the passage from the Bible in the Book of Judges [the source material for Handel] later on.

Artists or composers choose their subject – whether it be an extract from the Bible, like here, or a piece of history or mythology – and then use this as a vehicle to express something about humanity. So I began with the piece itself and expanded my research out from there.

Because fervour of religious self-belief is what motivates Jephtha, we investigated various religions and their various degrees of fundamentalism, Protestantism, orthodoxy, etc. We looked into various religious cults too. In search of a suitable ‘Ammonite’ society, to contrast with Jephtha’s uncompromising worldview as an ‘Israelite’, we explored the Enlightenment.

EG: Handel was writing at the time of the Enlightenment, a period of great doubt. How does the Enlightenment and indeed light – and darkness – play a role in this production, as Jephtha’s religious certainty is turned precarious?

SLH: God’s first commandment was ‘Let there be light’. Religion repeatedly uses concepts of light and dark as a metaphor. Similarly, the ‘Enlightenment’ is itself a reference to the emergence of intellectual thought from a period of darkness. Many people became enlightened intellectually, but they also experienced more light literally, due to advancements in oil lamp technology – and gas light was developed by the end of the 18th century. So light developed as both a metaphorical and real concept.

In this stage design, monumental walls suggest the state of Jephtha’s mind, his encroaching doubts and his fears. The walls move into various configurations and in doing so, they expose both light and dark spaces and cast long shadows. There is a monumental religiosity to these walls that suggests the hubristic weight of Jephtha’s vow to God.

As an oratorio, there was originally no scenery envisaged for the first Jephtha performances. We also had no desire to stage multiple cumbersome scene changes, so we opted for a staging which could be flexible – where we could create open and tight spaces, communal spaces, private spaces – and all of them fairly fluidly.

EG: You collaborated with Director Oliver Mears and Lighting Designer Fabiana Piccioli previously on Rigoletto. How has it been working together again?

SLH: We had a good working relationship while collaborating on Rigoletto, but that production followed a more usual process where the set design was largely achieved conceptually before Fabiana engaged with her lighting design. Because Rigoletto is more fixed in terms of its three clear scenic locales, it was simpler to take that approach. With Jephtha, we felt that the lighting design should be as elemental to the staging as the set design.

Here, we are using the lighting in an architecturally structural way. Oliver and Movement Director Anna Morrissey have been blocking the cast into stage positions whilst also carefully considering the characters’ positions either within or outside areas of light or shadow. I believe this is unusual, as usually the lighting design responds to both the directed staging and set design, not vice versa. Lighting design ideas were key to working up the set design right from an empty model. So we worked as a team, the three of us: Oliver, Fabiana and myself – the staging and lighting designs have worked together hand in hand from the start of this process.

EG: You’ve shared references which served as inspiration for the set design: Fan Ho’s Approaching Shadow (1954); William Hogarth’s Tavern Scene (1735), the third painting in his A Rake’s Progress series; several works by Richard Serra, including those in his 2016 Above Below Betwixt Between, Every Which Way, Silence (For John Cage), Through exhibition; and William Blake’s frontispiece to his poem Song of Los. Can you walk us through the influence of each on the production?

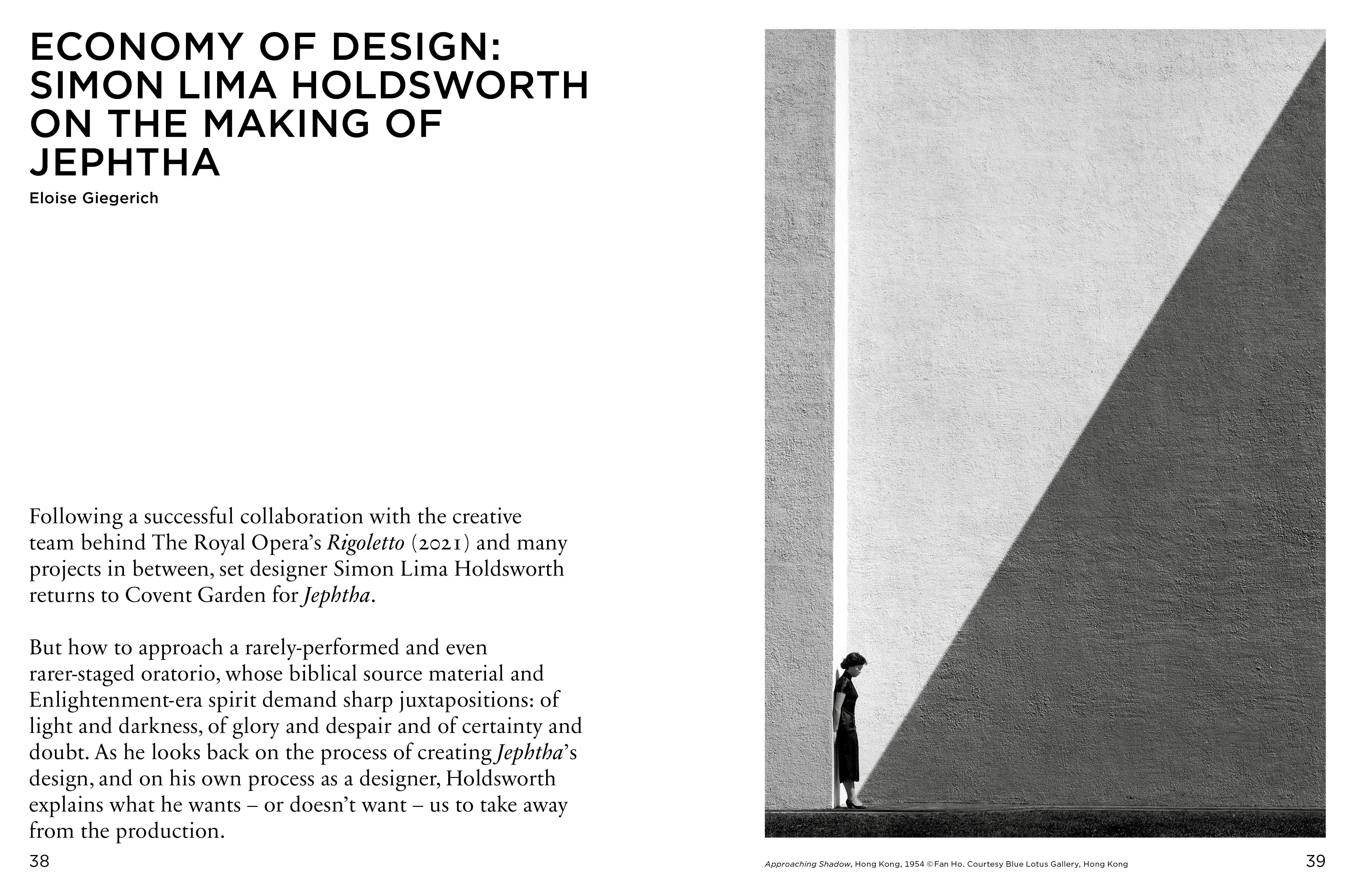

SLH: I picked Approaching Shadow because it’s the most extreme example of Fan Ho’s exploration of chiaroscuro through photography. You can get a sense of the shadows that we hope to achieve within the movement of the set design’s walls and how light and shadow might therefore slide and fall within the space. We also looked into the Light and Space art movement, which is a niche minimalist art movement. But Approaching Shadow really sums up what we were trying to achieve from the start; it spells out a strong narrative in terms of light and dark.

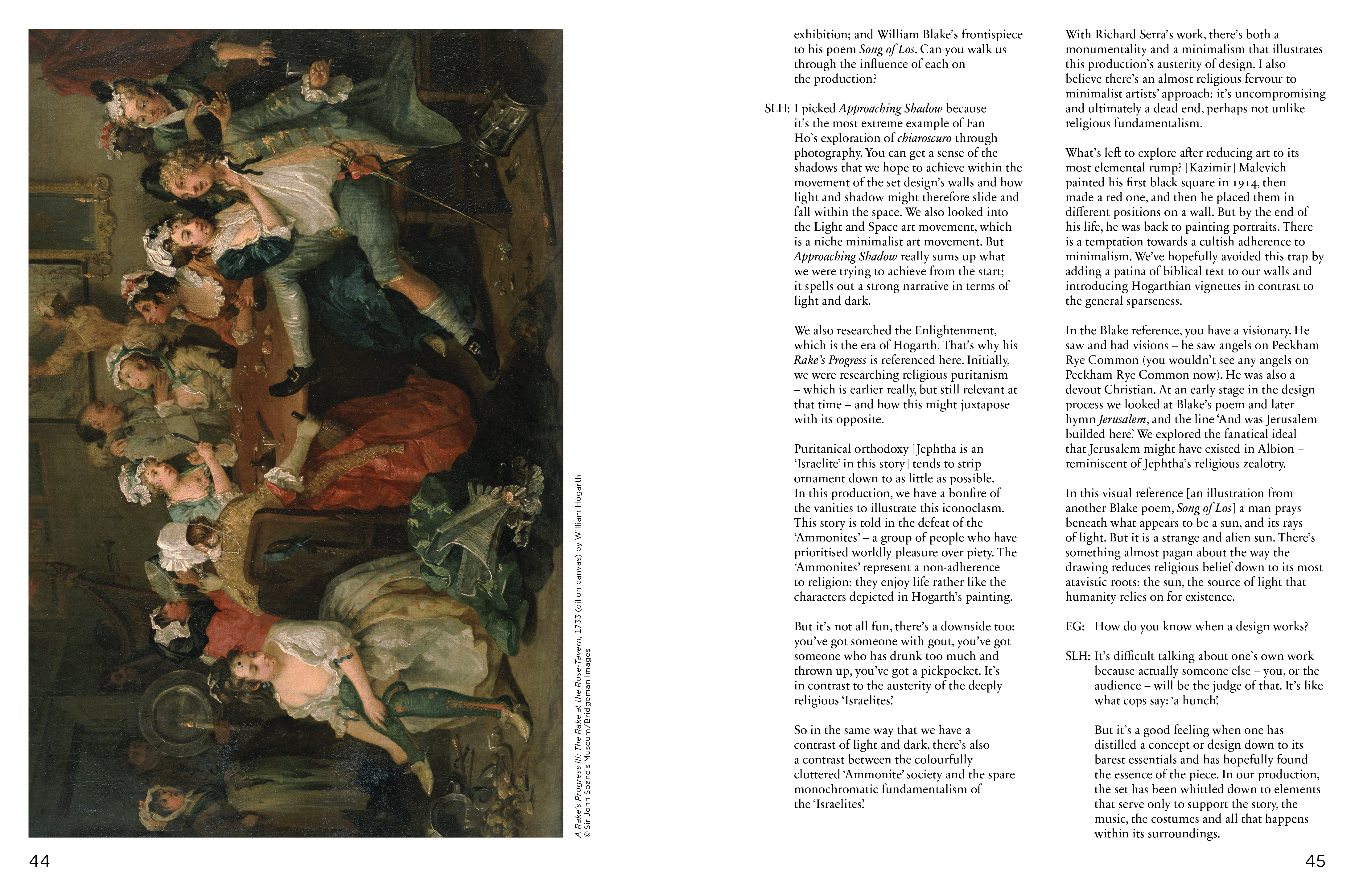

We also researched the Enlightenment, which is the era of Hogarth. That’s why his Rake’s Progress is referenced here. Initially, we were researching religious puritanism – which is earlier really, but still relevant at that time – and how this might juxtapose with its opposite. Puritanical orthodoxy [Jephtha is an ‘Israelite’ in this story] tends to strip ornament down to as little as possible. In this production, we have a bonfire of the vanities to illustrate this iconoclasm. This story is told in the defeat of the ‘Ammonites’ – a group of people who have prioritised worldly pleasure over piety. The ‘Ammonites’ represent a non-adherence to religion: they enjoy life rather like the characters depicted in Hogarth’s painting. But it’s not all fun, there’s a downside too: you’ve got someone with gout, you’ve got someone who has drunk too much and thrown up, you’ve got a pickpocket. It’s in contrast to the austerity of the deeply religious ‘Israelites’. So in the same way that we have a contrast of light and dark, there’s also a contrast between the colourfully cluttered ‘Ammonite’ society and the spare monochromatic fundamentalism of the ‘Israelites’.

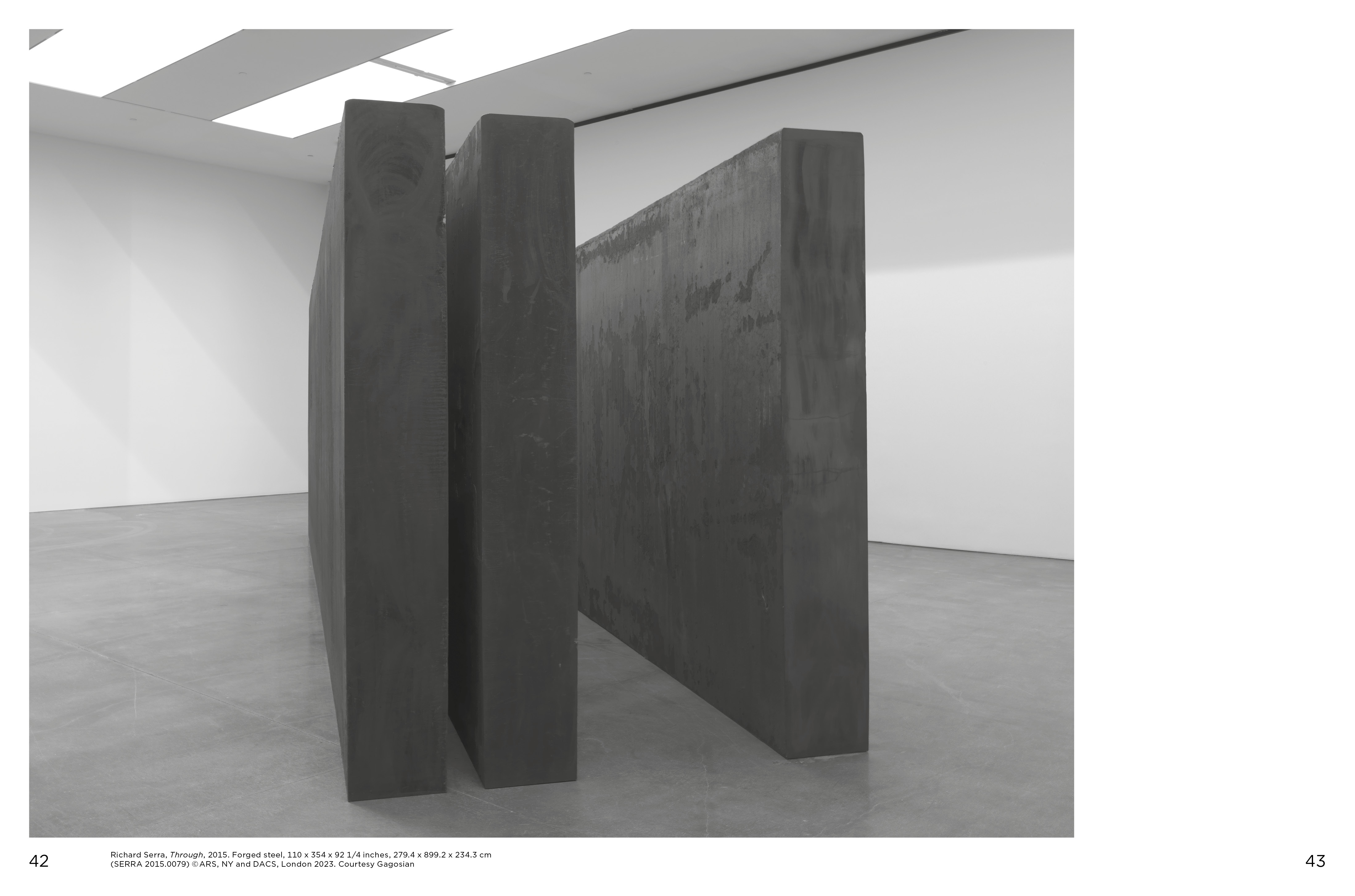

With Richard Serra’s work, there’s both a monumentality and a minimalism that illustrates this production’s austerity of design. I also believe there’s an almost religious fervour to minimalist artists’ approach: it’s uncompromising and ultimately a dead end, perhaps not unlike religious fundamentalism. What’s left to explore after reducing art to its most elemental rump? [Kazimir] Malevich painted his first black square in 1914, then made a red one, and then he placed them in different positions on a wall. But by the end of his life, he was back to painting portraits. There is a temptation towards a cultish adherence to minimalism. We’ve hopefully avoided this trap by adding a patina of biblical text to our walls and introducing Hogarthian vignettes in contrast to the general sparseness.

In the Blake reference, you have a visionary. He saw and had visions – he saw angels on Peckham Rye Common (you wouldn’t see any angels on Peckham Rye Common now). He was also a devout Christian. At an early stage in the design process we looked at Blake’s poem and later hymn Jerusalem, and the line ‘And was Jerusalem builded here’. We explored the fanatical ideal that Jerusalem might have existed in Albion – reminiscent of Jephtha’s religious zealotry.

In this visual reference [an illustration from another Blake poem, Song of Los] a man prays beneath what appears to be a sun, and its rays of light. But it is a strange and alien sun. There’s something almost pagan about the way the drawing reduces religious belief down to its most atavistic roots: the sun, the source of light that humanity relies on for existence.

EG: How do you know when a design works?

SLH: It’s difficult talking about one’s own work because actually someone else – you, or the audience – will be the judge of that. It’s like what cops say: ‘a hunch’.

But it’s a good feeling when one has distilled a concept or design down to its barest essentials and has hopefully found the essence of the piece. In our production, the set has been whittled down to elements that serve only to support the story, the music, the costumes and all that happens within its surroundings.

It’s also satisfying to be able to use the same elements repeatedly but in different ways. In addition to the walls, prop benches became more and more central to the design. It was satisfying to be able to use these benches as more than just props or benches. There is something uncompromisingly uncomfortable about a bench that worked well in this tale. And the vow, first written on a torn out page from a prayer book and then recurring nightmarishly throughout the production as Jephtha’s hubris comes back to haunt him, is another satisfying economy of design.

EG: What do you want the design of Jephtha to communicate to the audience?

SLH: I think it’s interesting when the design asks more questions than it answers. So perhaps I should be asking you the questions!

If you’re looking at something – the ‘sun’, for instance – one is momentarily engaged. But if that ‘sun’ develops or has an uncanny quality to it, it becomes engaging for a greater period of time and more compelling. I don’t believe it is the designer’s job to answer the questions raised by Handel and his librettist Morell, but rather to endorse those questions – or to pursue their inquiry further.