![]()

Finding Humanity in Otello

Year - 2022

Otello

Royal Opera House

Tenor Russell Thomas on performing the title role of Verdi's opera

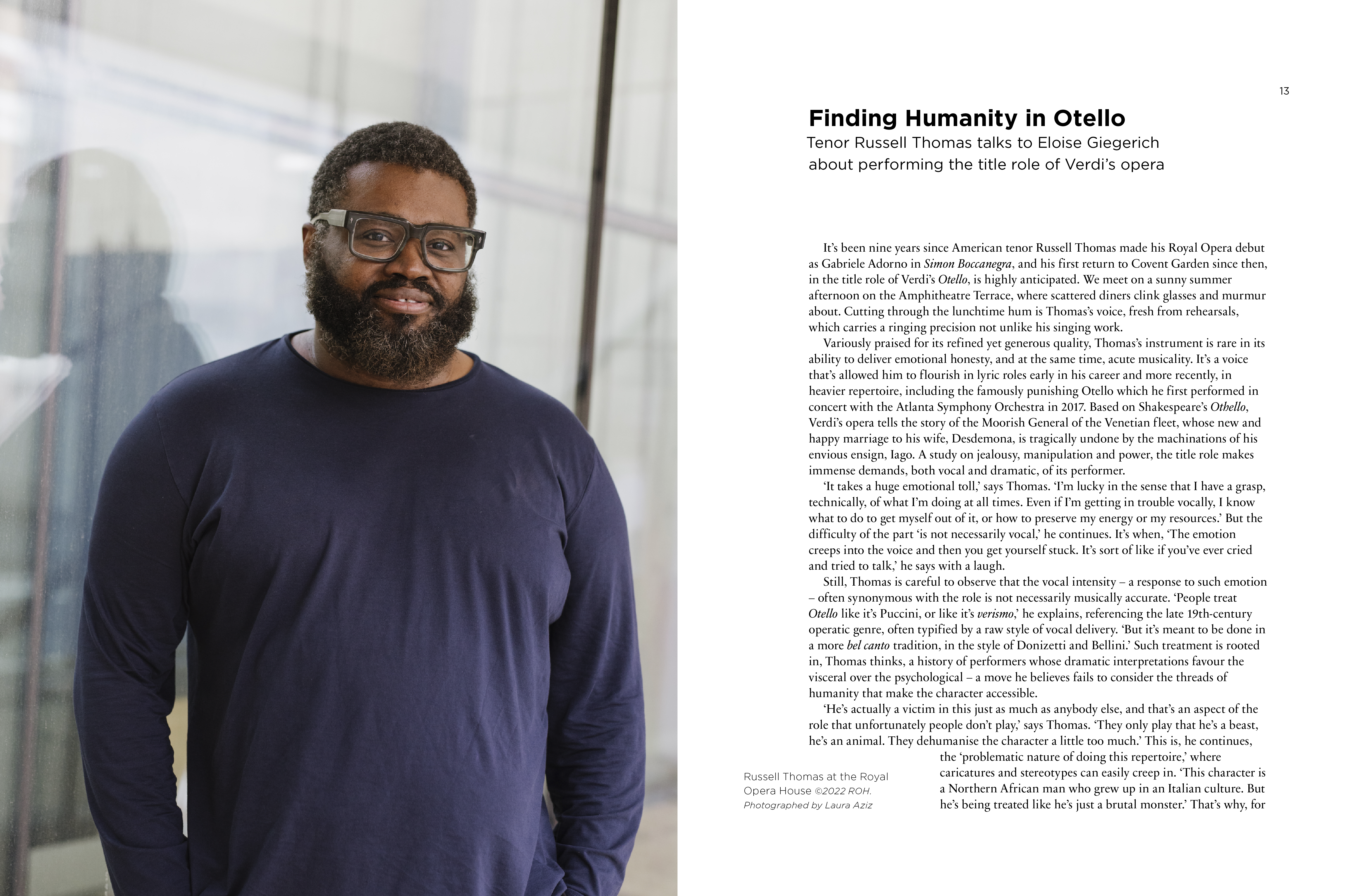

It’s been nine years since American tenor Russell Thomas made his Royal Opera debut as Gabriele Adorno in Simon Boccanegra, and his first return to Covent Garden since then, in the title role of Verdi’s Otello, is highly anticipated. We meet on a sunny summer afternoon on the Amphitheatre Terrace, where scattered diners clink glasses and murmur about. Cutting through the lunchtime hum is Thomas’s voice, fresh from rehearsals, which carries a ringing precision not unlike his singing work.

Variously praised for its refined yet generous quality, Thomas’s instrument is rare in its ability to deliver emotional honesty, and at the same time, acute musicality. It’s a voice that’s allowed him to flourish in lyric roles early in his career and more recently, in heavier repertoire, including the famously punishing Otello which he first performed in concert with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra in 2017. Based on Shakespeare’s Othello, Verdi’s opera tells the story of the Moorish General of the Venetian fleet, whose new and happy marriage to his wife, Desdemona, is tragically undone by the machinations of his envious ensign, Iago. A study on jealousy, manipulation and power, the title role makes immense demands, both vocal and dramatic, of its performer.

‘It takes a huge emotional toll,’ says Thomas. ‘I’m lucky in the sense that I have a grasp, technically, of what I’m doing at all times. Even if I’m getting in trouble vocally, I know what to do to get myself out of it, or how to preserve my energy or my resources.’ But the difficulty of the part ‘is not necessarily vocal,’ he continues. It’s when, ‘The emotion creeps into the voice and then you get yourself stuck. It’s sort of like if you’ve ever cried and tried to talk,’ he says with a laugh.

Still, Thomas is careful to observe that the vocal intensity – a response to such emotion – often synonymous with the role is not necessarily musically accurate. ‘People treat Otello like it’s Puccini, or like it’s verismo,’ he explains, referencing the late 19th-century operatic genre, often typified by a raw style of vocal delivery. ‘But it’s meant to be done in a more bel canto tradition, in the style of Donizetti and Bellini.’ Such treatment is rooted in, Thomas thinks, a history of performers whose dramatic interpretations favour the visceral over the psychological – a move he believes fails to consider the threads of humanity that make the character accessible.

‘He’s actually a victim in this just as much as anybody else, and that’s an aspect of the role that unfortunately people don’t play,’ says Thomas. ‘They only play that he’s a beast, he’s an animal. They dehumanise the character a little too much.’ This is, he continues, the ‘problematic nature of doing this repertoire,’ where caricatures and stereotypes can easily creep in. ‘This character is a Northern African man who grew up in an Italian culture. But he’s being treated like he’s just a brutal monster.’ That’s why, for Thomas, getting into Otello’s mindset – the nuances of his psychology – rather than leaning, purely, into the visceral, is so important. ‘Why does Otello react this way?’ he asks, referring to the character’s susceptibility to Iago’s lies about Desdemona, and the violent consequences of his jealousy. ‘He just stands around and listens to more and more, and it affects him deeply: he experiences a real downward spiral. I think my job at the end of the night is to make people feel sorry for him.’

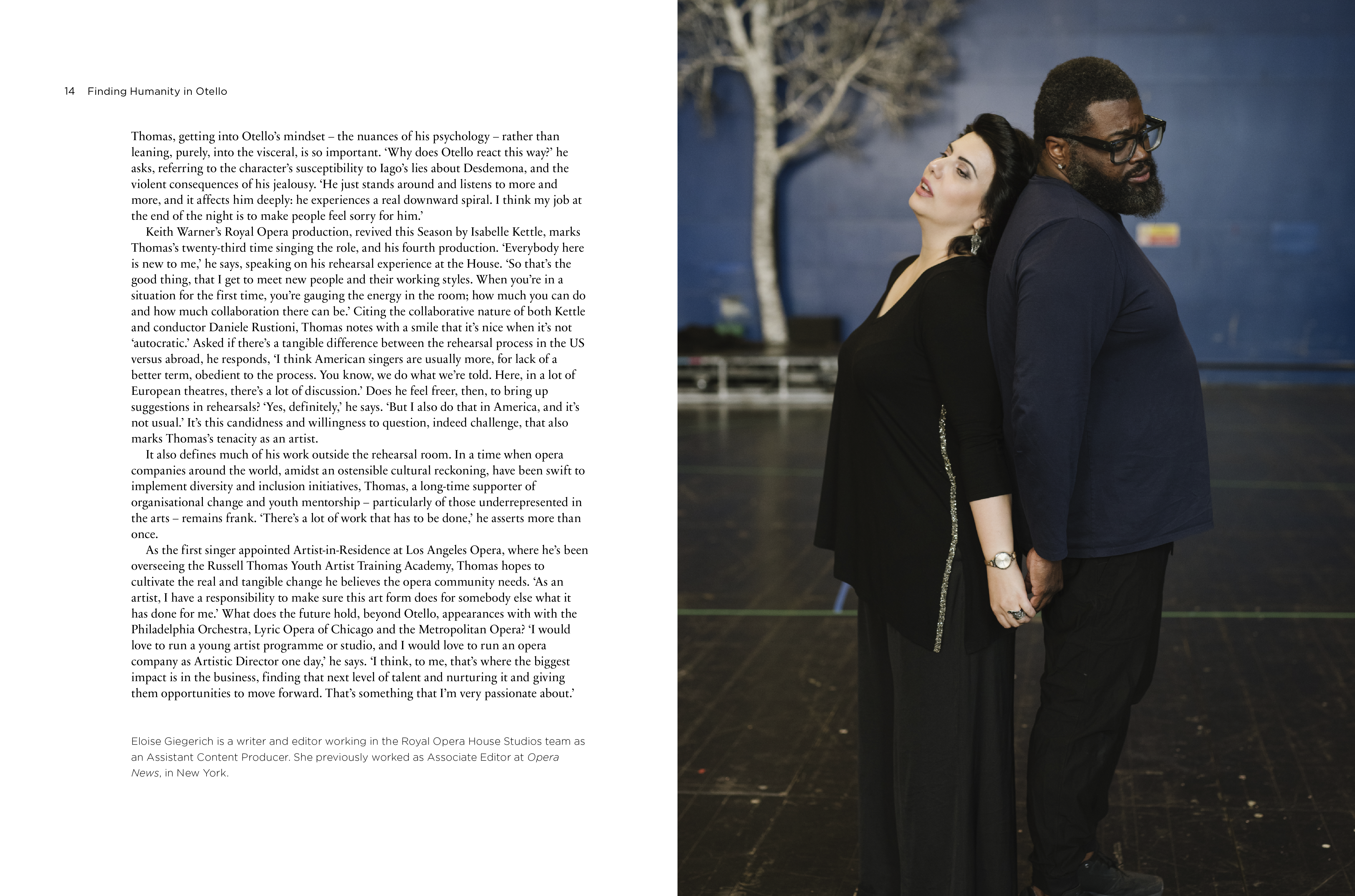

Keith Warner’s Royal Opera production, revived this Season by Isabelle Kettle, marks Thomas’s twenty-third time singing the role, and his fourth production. ‘Everybody here is new to me,’ he says, speaking on his rehearsal experience at the House. ‘So that’s the good thing, that I get to meet new people and their working styles. When you’re in a situation for the first time, you’re gauging the energy in the room; how much you can do and how much collaboration there can be.’ Citing the collaborative nature of both Kettle and conductor Daniele Rustioni, Thomas notes with a smile that it’s nice when it’s not ‘autocratic.’ Asked if there’s a tangible difference between the rehearsal process in the US versus abroad, he responds, ‘I think American singers are usually more, for lack of a better term, obedient to the process. You know, we do what we’re told. Here, in a lot of European theatres, there’s a lot of discussion.’ Does he feel freer, then, to bring up suggestions in rehearsals? ‘Yes, definitely,’ he says. ‘But I also do that in America, and it’s not usual.’ It’s this candidness and willingness to question, indeed challenge, that also marks Thomas’s tenacity as an artist.

It also defines much of his work outside the rehearsal room. In a time when opera companies around the world, amidst an ostensible cultural reckoning, have been swift to implement diversity and inclusion initiatives, Thomas, a long-time supporter of organisational change and youth mentorship – particularly of those underrepresented in the arts – remains frank. ‘There’s a lot of work that has to be done,’ he asserts more than once.

As the first singer appointed Artist-in-Residence at Los Angeles Opera, where he’s been overseeing the Russell Thomas Youth Artist Training Academy, Thomas hopes to cultivate the real and tangible change he believes the opera community needs. ‘As an artist, I have a responsibility to make sure this art form does for somebody else what it has done for me.’ What does the future hold, beyond Otello, appearances with with the Philadelphia Orchestra, Lyric Opera of Chicago and the Metropolitan Opera? ‘I would love to run a young artist programme or studio, and I would love to run an opera company as Artistic Director one day,’ he says. ‘I think, to me, that’s where the biggest impact is in the business, finding that next level of talent and nurturing it and giving them opportunities to move forward. That’s something that I’m very passionate about.’