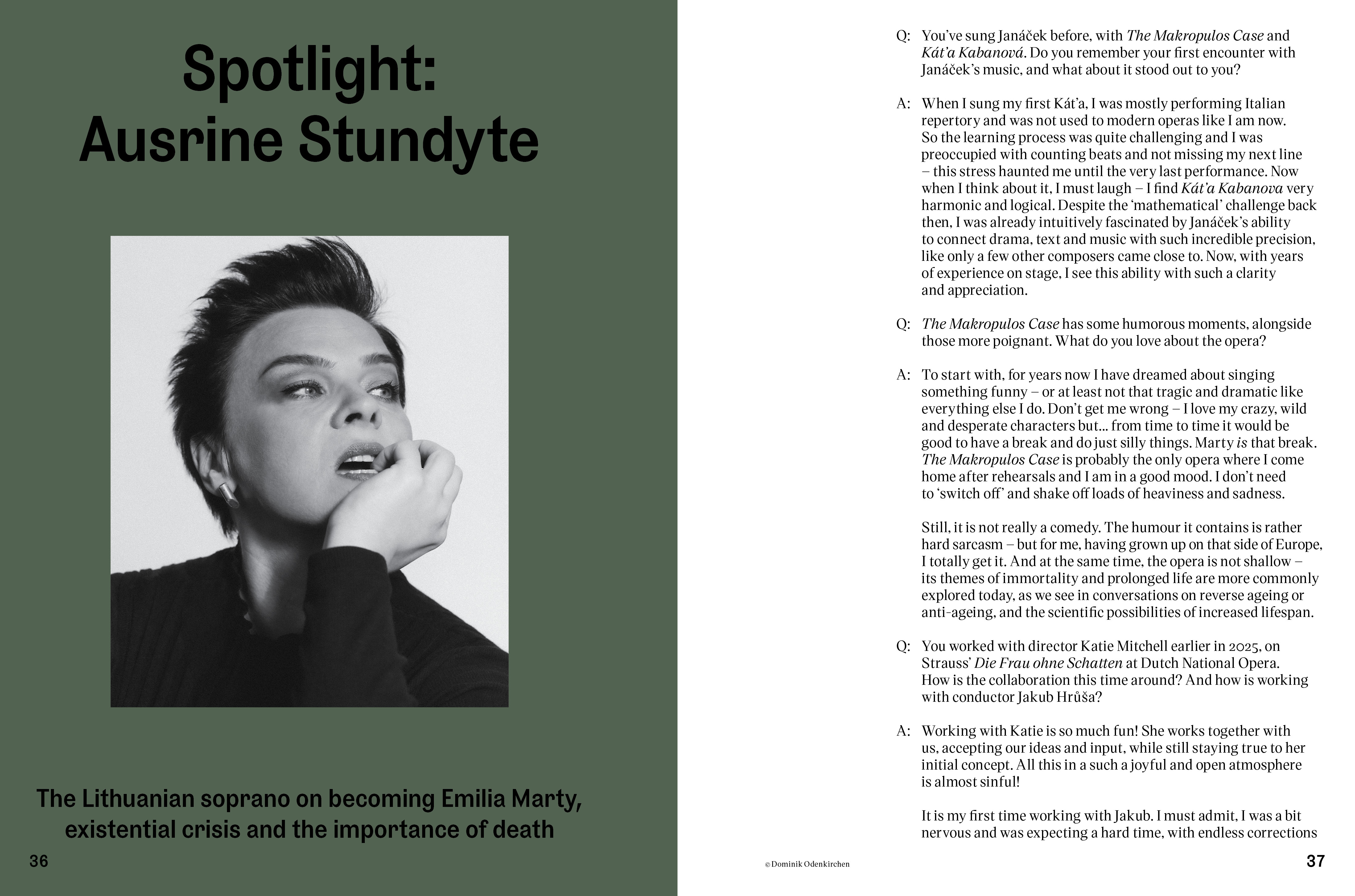

Spotlight: Ausrine Stundyte

Year - 2025

The Makropulos Case

Royal Opera House

The Lithuanian soprano on becoming Emilia Marty, existential crisis and the importance of death

Q: You’ve sung Janáček before, with The Makropulos Case and Kát’a Kabanová. Do you remember your first encounter with Janáček’s music, and what about it stood out to you?

A: When I sung my first Kát’a, I was mostly performing Italian repertory and was not used to modern operas like I am now. So the learning process was quite challenging and I was preoccupied with counting beats and not missing my next line – this stress haunted me until the very last performance. Now when I think about it, I must laugh – I find Kát’a Kabanova very harmonic and logical. Despite the ‘mathematical’ challenge back then, I was already intuitively fascinated by Janáček’s ability to connect drama, text and music with such incredible precision, like only a few other composers came close to. Now, with years of experience on stage, I see this ability with such a clarity and appreciation.

Q: The Makropulos Case has some humorous moments, alongside those more poignant. What do you love about the opera?

A: To start with, for years now I have dreamed about singing something funny – or at least not that tragic and dramatic like everything else I do. Don’t get me wrong – I love my crazy, wild and desperate characters but... from time to time it would be good to have a break and do just silly things. Marty is that break. The Makropulos Case is probably the only opera where I come home after rehearsals and I am in a good mood. I don’t need to ‘switch off’ and shake off loads of heaviness and sadness.

Still, it is not really a comedy. The humour it contains is rather hard sarcasm – but for me, having grown up on that side of Europe, I totally get it. And at the same time, the opera is not shallow – its themes of immortality and prolonged life are more commonly explored today, as we see in conversations on reverse ageing or anti-ageing, and the scientific possibilities of increased lifespan.

Q: You worked with director Katie Mitchell earlier in 2025, on Strauss’ Die Frau ohne Schatten at Dutch National Opera. How is the collaboration this time around? And how is working with conductor Jakub Hrůša?

A: Working with Katie is so much fun! She works together with us, accepting our ideas and input, while still staying true to her initial concept. All this in a such a joyful and open atmosphere is almost sinful!

It is my first time working with Jakub. I must admit, I was a bit nervous and was expecting a hard time, with endless corrections on my pronunciation, but so far it is going very well. He doses the amount of information into bites that we can chew, and has compassion and patience. The atmosphere is very nice and supportive – it is a real joy!

Q: You inhabit your roles with incredible dramatic intensity. How do you find the right balance between getting to the emotional heart of a character and controlling the voice?

A: This has always been the biggest challenge for me. I know so very well that in order to sing well, unfortunately I need to take space from the character. During rehearsals, though, I focus mostly on acting and don’t care about singing too much. In that period, the emotional life of a character finds its place in my body, and later, when orchestra rehearsals begin, I can focus on singing, as my body draws from the memory of the emotion, and is able to express the feeling naturally.

Q: Marty is not your typical soprano role, with her rich (and centuries-long) backstory. How do you get into the mindset of a woman who has lived for hundreds of years, and begin to understand and empathize with her? Do you share any characteristics with Marty?

A: In a way I am feeling a bit like Marty. Every decade for most of us brings some existential crisis, some shifts in values and goals. I am at the point in my life where all my biggest dreams that were my driving force – my torture and my fuel – are fulfilled. And even though I am immensely grateful and I appreciate every single bit of it – nothing came easy to me – there is a certain feeling of emptiness. I am someone who loves to dream and become obsessed with it. Now... I am fulfilled and calm. I feel like I could go already now, if needed. Sometimes I feel like Marty in the last five minutes of the opera, where she decides not to prolong her life with a second shot of magic elixir. But by now I know that after a year or so I will have readjusted my direction. This feeling will settle in, and be gone for another decade. At the moment, though, it serves me very well – especially for this role.

Q: Janáček writes about women, and the lives of women, in many of his operas. Can you speak on how he addresses not only the existential nature of living forever in The Makropulos Case, but of living forever in a world of men?

A: The way I see Marty is she knows men very well and plays them like a strategy – always reading the room, always three moves ahead, untouched and never getting too close. For Marty, masculine expression of violence is obviously a sign of desperation and a loss of control, not something to be afraid of or to be hurt by. It is sometimes unavoidable but it never makes her feel like a victim, rather it is like a bitter pill that needs to taken – not a big deal.

Her feelings towards life are, to me, similar to her feeling towards men. Bored. Untouched. Cold and tired of it all. Longing to feel something but not really trying anymore.

Q: You’ve stated before that, growing up, you had a fascination with death, and an understanding that death was not ‘the end’. In an opera like The Makropulos Case, where death – or the reverse, eternal life – is a central theme, what do you make of Marty’s end decision to forgo the elixir?

A: When I was younger, I often wondered – let’s suppose the concept of reincarnation is true – why, oh why do we need to have our memories of previous lives wiped out? How can we grow and evolve if we don’t remember mistakes we have made before, if we start again from complete zero?

But now I can see why. Maybe life is not about growing and getting better. Maybe life is about experience. And how could you experience that excitement of a small child visiting a circus or petting a rabbit if you could remember and know everything from past lives? How could you feel that crazy, stupid yet amazing teenage love if you could remember all failed relationships from before?

Maybe we won’t, but our children might have the possibility to live 200 or more years. But will that really be good? Is it not exactly this knowing that we have limited time – that scarcity of years and that urgency – that makes life precious, encounters special and connections fragile and worth sacrifice? When you have unlimited time, you stop caring and you get bored. If this doesn’t work out, another go probably will... Too much choice is not good for humans!

Maybe for Marty, in order to want to keep living, she needs to have her memories erased – but that is what death does.

Q: In disappearing into a role onstage and becoming your character so fully, how is it when the run of a production is over? Will Marty stay with you for some time?

A: Absolutely. I always carry my characters with me for several weeks, until they are replaced with the next one I am working on. While most of the time this is not a good feeling, I will keep Marty with me with pleasure!